The explosion of the space shuttle Challenger on Jan. 28, 1986, remains one of the worst accidents in the history of the American space program. Two other major fatal space program catastrophes also occurred within a few calendar days of the Shuttle Challenger disaster date: the Apollo 1 fire on January 27, 1967 that killed 3 astronauts, and the Shuttle Columbia disintegration on February 1, 2003 that killed 7 astronauts.

I shared some personal reflections of the Challenger event and its connections to data science in two articles. Here are excerpts from those two publications:

(1) Absence of Evidence is not the same as Evidence of Absence

In the era of big data, we easily forget that we haven’t yet measured everything. Even with the prevalence of data everywhere, we still haven’t collected all possible data on a particular subject. Consequently, statistical analyses should be aware of and make allowances for missing data (absence of evidence), in order to avoid biased conclusions. Conversely, “evidence of absence” is a very valuable piece of information, if you can prove it. Scientists have investigated the importance of these concepts in the evaluation of substance abuse education programs. They find that even though the distinctions between the two concepts (“evidence of absence” versus “absence of evidence “) are important, some policy decisions and societal responses to important problems should move forward anyway. This is an atypical case.

Usually the distinctions between the two concepts (Absence of Evidence versus Evidence of Absence) are significant influencers in decision-making and in the advancement of an area of research.

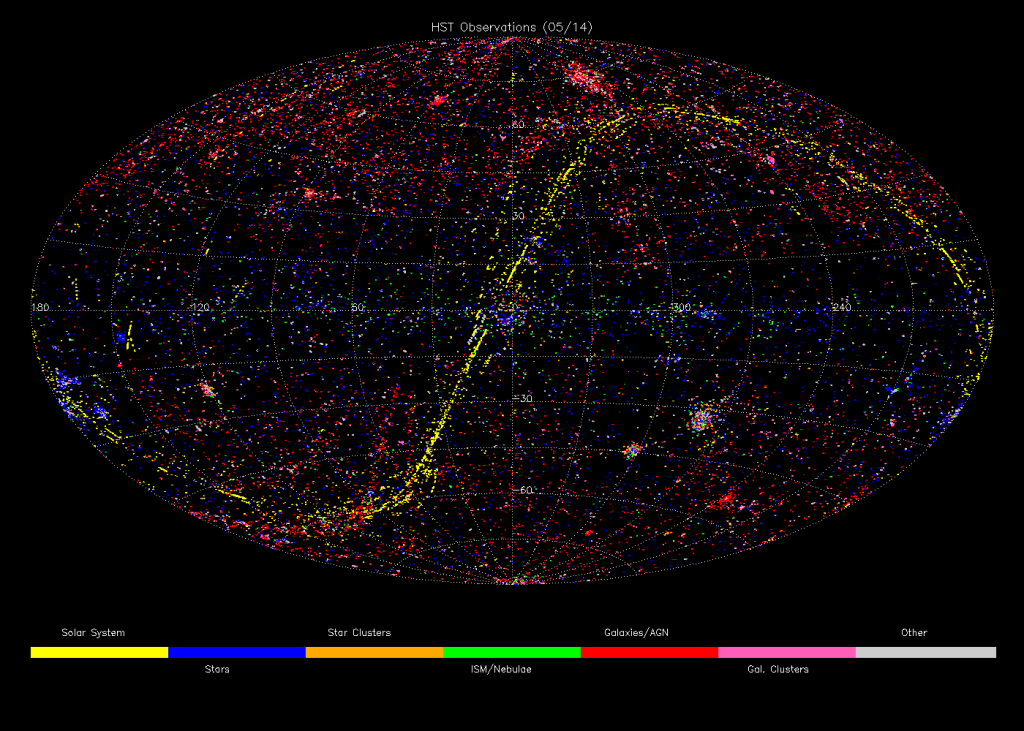

For example, I once suggested to a major astronomy observatory director that we create a database of things searched for (with his telescopes) but never found – the EAD: Evidence of Absence Database. He liked the idea (as a tool to help minimize redundant usage of his facilities for duplicate false searches in cases where we already have clear evidence of absence), but he didn’t offer to pay for it. Here is one science paper that has dramatically understood this concept: “Can apparent superluminal neutrino speeds be explained as a quantum weak measurement?” The paper’s full complete abstract: “Probably not.”

A more dramatic and ruinous example of a failure to appreciate this statistical concept is the NASA Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986, when engineers assumed that the lack of evidence of O-ring failures during cold weather launches was equivalent to evidence that there would be no O-ring failure during a cold-weather launch. In this case, the consequences of faulty statistical reasoning were catastrophic. This is an extreme case that clearly demonstrates that “Absence of Evidence is not the same as Evidence of Absence” is an important statistical truism that we must never forget in the era of big data.

(read my full article at http://www.statisticsviews.com/details/feature/4911381/Statistical-Truisms-in-the-Age-of-Big-Data.html)

(2) A Growth Hacker’s Journey – At the right place at the right time

A few months after my arrival at the Hubble Telescope Science Institute in 1985, tragedy struck! In January 1986, the Shuttle Challenger exploded 78 seconds after launch, killing all 7 astronauts on board. As a young person who dreamed of working in astronomy and space sciences since I was 9 years old, I was devastated. It took weeks for the staff to recover from the trauma of that horrific day. To this day, I still get choked up when I watch the recorded video footage of the event. Three things became very clear during those after-months:

- The Shuttle launches would not resume for several years (hence, the Hubble Telescope would be grounded for all those years) while NASA fixed the problems that led to the Challenger catastrophe, which meant that the Hubble team of scientists and engineers had a lot of years to evaluate and improve all of the telescope systems.

- One of the systems that was in significant need of improvement was the administrator-oriented Hubble Data Management System, which was previously designed primarily for data management by data system administrators and not designed so much for scientist-friendly data access, exploration, and discovery — hence, during those post-Challenger years, fresh designs and plans were developed for a new “top of the line” scientist-oriented user-friendly Hubble Science Data Archive.

- Another system was identified as needing total overhaul, even rewriting the entire code base from scratch, and that was the scientific proposal entry, processing, and reporting system — they needed someone new to do the job, someone with a fresh perspective, with database skills, user interface skills, programming skills, and strong familiarity with astronomy. Guess who satisfied all of those constraints?

(read my full article at https://www.mapr.com/blog/growth-hackers-journey-right-place-right-time)

Follow Kirk Borne on Twitter @KirkDBorne